Sidebar: The Big Bang Horizon Problem

The horizon problem is well known and has been well described by many. So rather than re-invent the wheel and create yet another description, I instead present one of the clearer descriptions I've found. This is clip from the The Universe - episode Light Speed1 where they present a very clear description of the Horizon problem. For your convenience I've also provided a transcript of the video below.

Transcript:

Narrator:

This breath taking shot is the Hubble space telescope's ultra deep

field. It's a massively detailed photo of an area of the sky a hundred

times smaller than the fool moon, yet containing ten thousand galaxies.

Some whose light has been speeding toward us for 13 billion years.

Beyond them is the cosmic background radiation from just 400,000 years

after the big bang. In NASA's color coded picture the radiation's glow

is pure green representing a distribution of matter so uniform, its

temperature varies varies no more than 1/50,000 of a degree. Nothing in

human experience is even close to this kind of uniformity. In fact

astronomers believe the universe should really be very different.

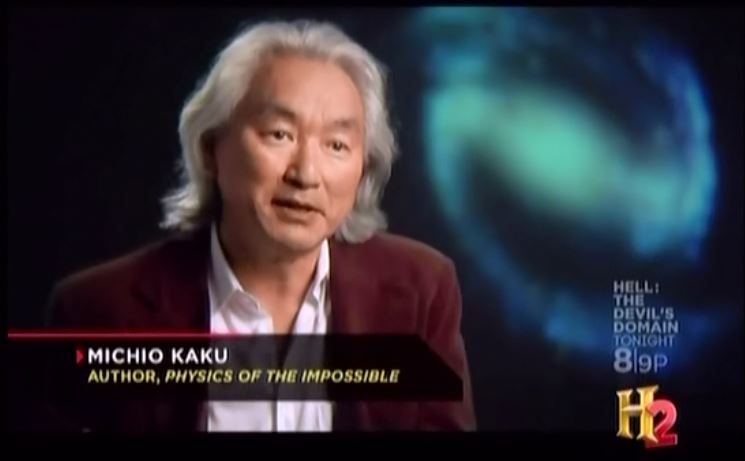

Michio Kaku (Author, Physics of the Impossible):

"By rights the universe should be lumpy. If you look in this direction

[pointing

forward] and you look in that direction [pointing backward] you should

see two

entirely different concentrations of matter, different temperatures. But

it's

extremely uniform. Therefore we have a puzzle.

Narrator:

"The puzzle has its roots in the universe's birth at the big bang. If

everything

flew apart from the beginning, why shouldn't it be uniform?

Alan Guth,

MIT:

"No kind of explosion that we know about leads to that kind of

uniformity. If you

imagine an ordinary explosion - an atomic bomb, a piece of TNT, it's not

really

uniform at all. There's pieces of shrapnel going off there, pieces of

paper going

of there, an extra piece of iron going off there. Its really very

non-uniform."

Narrator:

"So scientists believe the cosmic background radiation just shouldn't be

as smooth

and green as it is. We can find out why in an ordinary paint store."

Amy Mainzer, NASA/JPL:

Let's consider a universe that consists of different colored cans of

paint. In our

hyperthetical paint universe, we have a can of yellow paint and a can of

blue

paint. ANd at the instance of the big bang in this universe, two cans of

paint

start expanding apart from each other. In our hyperthetical paint

universe, one

side of it would look yellow, and the other side would look blue."

Narrator:

But as we learned, the cosmos looks green, whether it's the paint

universe or the

real thing. The two colors of paint represent the different particles of

the

infinite universe. To end up a uniform green, like the cosmic background

radiation, they had to be touching. But when scientist first calculated

the speed

of the big bang, they concluded that it blew everything apart faster

than the

speed of light. Meaning blue and yellow were too far apart, even at the

instant of

creation for any mixing to take place.

Amy Mainzer:

"Seeing a universe that's so uniformly green would be very strange. It

would be

like taking our can of yellow paint, pouring it out and having it be

green. Then

taking the can of blue paint, pouring it out, and having it be green as

well. It's

impossible."

Guth:

This horizon problem can be solved by a theory I worked on called

inflation. Which

is a twist on the big bang."

1 The Universe episode Light Speed, History Channel Documentary, 2008